Has Microsoft Made a Huge Strategic Blunder with Cortana?

I asked my 10-year son what he thought of this composite photo of intelligent assistants. He said, “Neat! But kind of creepy…”

Creepy is a word that frequently travels with intelligent assistants. It’s easy to identify one source of the creepiness, in how we’re presenting these machines as people.

Personification is a powerful creative device. When we attribute a human form or personality to things that are not human, it can make the product more accessible and easier to understand.

In the realm of intelligent assistants, however, this strategy is risky. Like lipstick on a pig, the risks surface not only in how these machines are represented, but also in how they behave.

Worse, once personification is embraced, even giants like Microsoft may be unable to dig their products out of the morass of challenges that inevitably follow.

Personification of Intelligent Assistants Is Rampant

As explored in my market analysis, product developers are crowding around the strategy of personification. The conceptual model for the vast majority of intelligent assistants is that of a human being.

Whether in intelligent assistants, robots, agents, bots, or avatars, personification is rampant. Need convincing? Just ask Siri, Cortana, Eliza, Nina, Iris, Robin, Jeannie, Donna, Amy, Alice, Cloe, Eva, Jeeves, or the countless other intelligent assistants presently under development.

What’s The Problem With Personifying Your Intelligent Assistant?

There’s nothing inherently wrong with personification. When well executed, it’s highly effective.

When misapplied, personification drives a visceral negative response. We don’t feel that way when cars, trains, drinks, or pastry dough are personified, but we do with intelligent assistants.

To understand why, we need to dig deeper, beyond the surface level appearances.

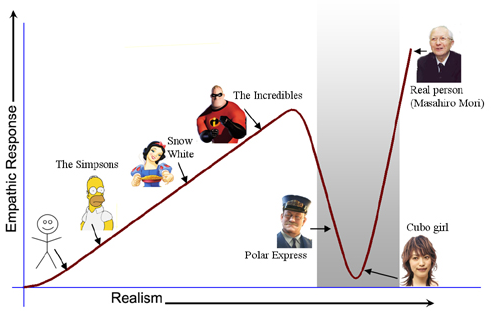

The uncanny valley applies to behaviours, not just appearances

Many intelligent assistants are presented as cartoon figures, presumably to manage our expectations for the product as “artificial people” and avoid the uncanny valley.

However, the trap of the uncanny valley applies not only to how assistants look, but also how they behave.

Intelligent assistants are smart machines, but they are not intelligent by human standards. And they are tools, utterly subservient. When intelligent assistants look like Cinderella but behave like Frankenstein or Igor, people may feel repulsed.

That’s the morass of personification. The behaviours of intelligent assistants may be too close to human to be safely personified.

Personification can be offensive

Why are so many intelligent assistants modelled after women?

I’m not here to explore this question, only to highlight it as a matter of product strategy.

Once you decide that your intelligent assistant is modelled after a human, you need to have a good answer to the question, What kind of person best represents this dumb, subordinate machine?

No amount of execution can improve or defend your product if the very idea of it is offensive to people.

Personification inflates our expectations

So can we just sidestep the problem by avoiding the use of women as intelligent assistants? Just Ask Jeeves, the answer is probably not. Personification inflates our expectations of the capabilities of intelligent assistants, regardless of the gender.

While it might be fun to call your phone Jarvis or Alfred, once the initial giggles subside, you’re left with a product that in no way behaves like those characters.

For some, the heightened expectations of personification lead to disillusionment. We expect them to be smart, funny, and highly effective. We’re left with the feeling that they’re merely imposters.

And that’s a shame. Cast in some other, less lofty conceptual model, the capabilities of the product might otherwise delight us. But you can’t promise me fillet mignon and be surprised at my disappointment when you serve me hamburger.

Personification is beyond our technical capabilities

Some might write-off this criticism of personification as a failure in execution, not a question of strategy. We just need to refine the underlying capabilities or tweak the experience to get back on track.

Engineers are embracing the challenge. As we emerge from this latest AI winter, many believe we can build human-like intelligence, provided we narrow our focus to specific domains of knowledge and clearly defined tasks. However, there’s an intrinsic contradiction in this statement.

It’s true, you can make the problem of building a human-like intelligence smaller by focusing on smaller and more specific tasks. But the question here is, Can you do it and still maintain the personification constraint, the illusion of a whole person? Making the product smaller makes it less human, not more.

Consider the analogy of an assembly line worker. We might say their work is so task-specific and repetitive it could be accomplished by a robot. However, we would rightfully draw fire if we said that the assembly line worker is a robot.

If we apply personification to robot-like tasks, aren’t we merely inverting the injustice applied to the assembly line worker? We’ve built a robot and we’re pretending it’s a person.

Cortana: “Personification problem? What problem?”

For the large players and their seemingly limitless resources, time may be all they need to sort this out.

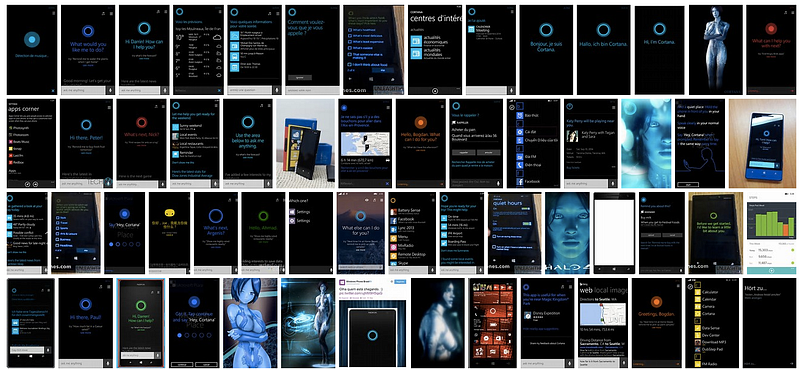

Microsoft, for example, is incorporating many artificial intelligences under the umbrella of the Cortana interface: Q&A, image recognition, chatbot, dictation, and the ability to remember and retrieve everything. In time, if not immediately, many people would regard the product as intelligent by human standards, even superhuman.

The character that shares Cortana’s name is a queen, a powerful ruler, not a servant. Cortana’s team has invested heavily in learning all the necessary yet sufficient attributes of professional personal assistants, including aspects of personality and the subtleties of human interactions.

All laudable investments.

Yet as demonstrated by a simple image search, Microsoft may always face an uphill battle trying to advance these product values while working within the conceptual model of Cortana.

What About Google Now?

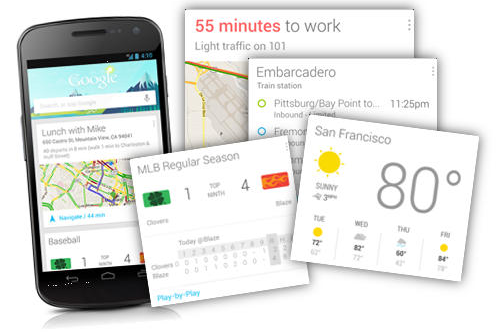

Google has vast financial resources and expertise in artificial intelligence. Many regard Google Now as even further along the evolutionary path than Cortana. Are they daunted by the challenge of personification?

You bet they are. As reported by Steven Levy on Medium:

Google’s search design lead [Jon] Wiley says that in order to pull off the illusion of speaking to a conscious entity, properly, you would need to automate a Pixar-level mastery of storytelling.

“I think we’re a long way from computers being able to evoke personality to the extent that human beings would relate comfortably to it.”

Lessons for Product Leaders?

If personification is such a minefield, even for the largest companies, perhaps these smart machines should just be emptied of their metaphors and conceptual models. Assistants like Google Now are embracing this do-no-harm strategy, to their advantage.

Should small companies, with our comparatively meagre resources, do the same?

My basketball coach used to say, If you don’t know what to do with the ball, don’t shoot! If your first inclination is to model your intelligent assistant after a person, consider Google’s do-no-harm strategy before you venture down that path.

Unfortunately, in following Google’s example, you may be forsaking advantages that are critical to success, particularly for smaller players. A strong conceptual model of your product is a tremendous asset. Cortana is Cortana instead of Microsoft Now because they want people to connect with it on a human level.

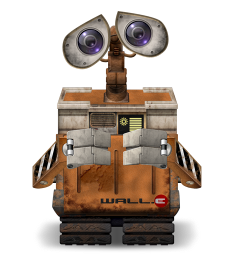

In the same spirit, if you can find your WALL-E, a way to represent your robot with authenticity that doesn’t overstep its technical capabilities, then by-all-means shoot!

What are the best models for intelligent assistants? Are they robots, animals, machines, or something entirely different? Do we even need to know they exist at all? Do you side with Google or Microsoft? I’d love to hear your thoughts.